This is one in a series of posts where the content is provided by a guest who has graciously answered five questions about their experience as a Tolkien reader. I am very humbled that anyone volunteers to spend time in this busy world to answer questions for my blog, and so I give my sincerest thanks to Richard and the other participants for this.

To see the idea behind this project, check out this page

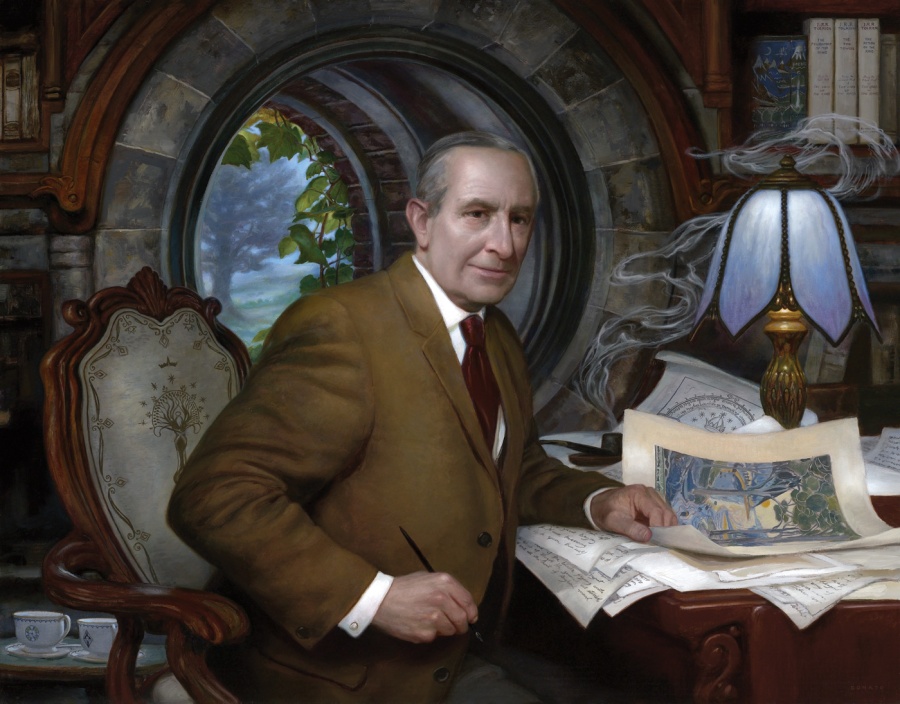

I want to thank Donato Giancola for allowing me to use his stunning portrait of J.R.R Tolkien as the featured image for this project. If you would like to purchase a print of this painting, they are available on his website!

If you would like to contribute your own experience, you can do so by using the form on the contact page, or by emailing me directly.

Now, on to Richard Rohlin’s responses:

How were you introduced to Tolkien’s work?

I read The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings a couple of years before the Peter Jackson films came out. I actually found a couple of old yellowed Del Rey paperbacks (of The Hobbit and The Fellowship of the Ring; I’ve always assumed they must have been left there by the previous owners) in the attic of the house we were living in at the time. I was nine or ten years old, and although I was a big Narnia fan at the time I’d never heard of these books. I took them downstairs to my mother, and she looked at them and said, “yeah, those are good.” Over the course of a summer family road trip from Texas to Tennessee, I read through both volumes. It was only when I came to the end of The Fellowship of the Ring that I realized there were at least two more volumes!

What is your favorite part of Tolkien’s work?

I think Tolkien was vastly underappreciated as a poet, by which I mean specifically a versifier. I didn’t really get the poetry my first, second, or third time through, but that’s been one of the many ways I’ve “grown into” the books. And of course elves. I can’t get enough of elves.

What is your fondest experience of Tolkien’s work?

One of the great moments in my life came when I was twelve years old and learned of the existence of The Silmarillion. My mom took me to the library to find a copy, and I ended up coming up with a copy of Unfinished Tales as well. There are certain books you read that set your tastes for the rest of your life, books that cause your imagination to turn a corner. The Silmarillion is one of those books for me.

Has the way you approach Tolkien’s work changed over time?

I am (thanks to Tolkien) a Germanic philologist, currently finishing my thesis on Eddic poetry and specifically an Eddic poem known as “The Waking of Angantýr.” My interest in philology began as an attempt to see Tolkien’s sub-creation through his eyes, and then discovering that I actually enjoyed this sort of work. I think there are lots of linguists and medievalists with similar stories. That experience, following in his academic footsteps as it were (or at least trying to – they’re rather large footprints), has certainly enriched my reading of his works. On the other hand, it’s freed me up to really read them again. There’s this phase that I think many Tolkien fans go through, usually right after they read The Silmarillion, where they are sure that they’ve got Middle-earth completely “figured out.” They know what categories and boxes to fit everyone into, they know what all of the allusions in The Lord of the Rings mean, etc. In that way the illusion that the Silmarillion creates is almost too effective. It’s only when you dig deeper into the complexity and the richness of Tolkien’s language creation, his mythmaking, his poetry, and the long and complicated textual history of the legendarium as it’s presented to us in The History of Middle-earth that you get a sense for how much there is. With that realization comes a certain freedom. I can relax. I can sit back and enjoy the story, the rich prose, the humor, the fullness that is there to be enjoyed. And I can know that I don’t have to get to the bottom of it all today. I probably never will. I don’t have to deconstruct it. I can set my mind free to rove “over hill and under tree.”

Would you ever recommend Tolkien’s work? Why/Why not?

Tolkien’s books are among the most life-changing works I have ever encountered. They set the trajectory for what my life, work, study, and faith have become. That said, I’ve found that it doesn’t always pay to recommend them too strongly to your friends. The sheer amount of investment which Tolkien “superfans” put into Middle-earth can be off-putting, even intimidating, to people considering their first casual read. Tolkien’s prose, which I find rich and lovely, does intimidate some readers of the “Harry Potter” generation (my generation)—no slander to Harry Potter intended! Oddly, I have found that the Generation Z kids (many of whom did not grow up with the films) are often much more excited and receptive about reading Tolkien. I wonder if his works are undergoing a “rediscovery” in a small way? I hope so. To children or adults, I would say simply this: Read these books. They may not change your life. They may not be your favorite thing in the world. But at the very least, you will leave Middle-earth richer than when you arrived.

To see more of Richard Rohlin’s thoughts on Tolkien, head over to his blog: http://blogonthebarrowdowns.blogspot.com/