I have seen several news stories along the lines of “books to read before seeing Tolkien” around the internet recently. While I applaud news outlets for encouraging reading tied to movies, several of these posts, though certainly not all, recommend reading Tolkien’s fantasy works instead of reading works about Tolkien. In my experience, biographical material is far more interesting to read before a biopic, so I have compiled a list of recommended (and not recommended) readings that appeal more to that aspect. Enjoy!

Recommended

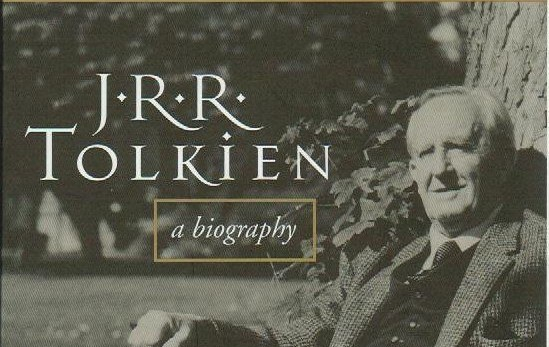

J.R.R. Tolkien: A Biography by Humphrey Carpenter

Put simply, this book is regarded as the essential Tolkien biography by many scholars and fans.

The Inklings: C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, Charles Williams and Their Friends by Humphrey Carpenter

This book focuses more specifically on the group that came together to share readings and community in Oxford that included Tolkien and Lewis.

Winner of the 1982 Mythopoeic Award for Inklings Studies!

Bandersnatch: C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, and the Creative Collaboration of the Inklings by Diana Pavlac Glyer

This is another well-respected and informative book looking at the creative group in Oxford!

I believe this is somehow related to her other text The Company They Keep, but as I have not read it I can provide no commentary. (Winner of the 2008 Mythopoeic Award for Inklings Studies.)

Tolkien and the Great War: The Threshold of Middle-earth by John Garth

This excellent book looks at Tolkien’s war experience during World War I and how his friendships and experience could have shaped his life and literature.

Winner of the 2004 Mythopoeic Award for Inklings Studies!

Tolkien and C.S. Lewis: The gift of Friendship by Colin Duriez

This is an even closer portrait of the friendship between Lewis and Tolkien, as the title implies.

The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien edited by Humphrey Carpenter

This is an invaluable resource for readers who want a little insight into Tolkien’s exchanges with friends, family, publishers, and fans.

Perilous and Fair: Women in the Works and Life of J.R.R. Tolkien edited by Janet Brennan Croft and Leslie Donovan

Even though this is a collection of essays rather than a book-length investigation, it is absolutely worth mentioning because it is perhaps the best resource available discussing the way that Tolkien worked with and supported women in his life.

Tolkien, Race and Cultural History by Dimitra Fimi

While not a biography, per se, this volume contains an insightful cultural history of Tolkien which is helpful when trying to understand how Tolkien’s views and opinions compared to the culture in which he lived.

Winner of the 2010 Mythopoeic Award for Inklings Studies!

The J.R.R. Tolkien Companion and Guide: Boxed Set

I added this after Jason Fisher and others pointed out that the Chronology is a fantastic insight into Tolkien’s biography.

Tolkien: Maker of Middle-earth by Catherine McIlwaine

Released in conjunction with the recent (2018) Tolkien exhibition in Oxford, this serves as both the catalogue for that exhibition and a remarkable text full of insight into the life of Tolkien.

Have Not Read

For each of these, I welcome comments from other readers!

Tolkien at Exeter College by John Garth

The Fellowship: The Literary Lives of the Inklings: J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Owen Barfield, and Charles Williams

Winner of the 2017 Mythopoeic Award for Inklings Studies!

Tolkien by Raymond Edwards

A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War by Joseph Loconte

Not Recommended

The Biography of J.R.R. Tolkien: Architect of Middle-earth by Daniel Grotta

Grotta has been exposed for, shall we say, taking liberties?

J.R.R. Tolkien (Just the Facts Biographies or Learner Biographies) by David R. Collins

Not well circulated, this book is intended as an introduction to the author for children. Unfortunately it suffers from two faults: it contextualizes the author using the movies, and at times it seems to take facts from Grotta.

Honorable Mentions

I have not included these in the list because I did not think them either bibliographic enough, or far-ranging enough in their bibliographic content. However, I wanted to mention some other works of great scholarship that touch on bibliography:

The several volumes produced by Hammond and Scull about Tolkien’s artistic output!

Shippey’s first and second books on Tolkien have less biography, but demonstrate overlap between biography and his creative output (credit to commenters for convincing me to add this).

Ring of Words: Tolkien and the Oxford English Dictionary by Peter Gilliver et al.

Tolkien in East Yorkshire 1917-1918: An Illustrated Tour by Phil Mathison

Tolkien and Wales: Language, Literature and Identity by Carl Phelpstead

There are several works by authors like Richard Purtill, Joseph Pearce, or Bradley Birzer which focus specifically on the religious aspects of Tolkien’s life and elevate it above all others. I have not included such works in this list, but a couple are worth hunting down if these are of interest to you.

What other books would you recommend for biographical information? Do you agree or disagree with anything on this list? Let me know!