It is still very clear in my mind that I considered the hobbits to be children during my first reading of LotR. In fact, I remember the animosity I initially felt toward the portrayal of the hobbits in the Peter Jackson films because they showed the hobbits as (what I deemed at the time) weak adults, instead of as an inexperienced, sheltered, child-like race. I will readily admit that I probably adopted this viewpoint to better relate to the hobbits as a reader, but it seems to be a very supportable perspective. I want to go into more detail with the character of Pippin in a separate blog post, he has long been my favorite hobbit, but I want to give just a small vignette of each hobbit here that bolster this approach to the hobbits as a group. Now that I am older, I can read into the nuances of characterization much more than I was able to in my first reading. I am not saying that the analysis that follows is the only way or the right way to approach the text, in fact I would explicitly say that some of the analysis is the wrong way to approach the text, but in my first reading I assumed that the hobbits were child-like, and so many aspects that otherwise would contribute to a different understanding of the group only served to validate that perspective in my first reading.

One of the shortcomings in my understanding of LotR as a young reader was that I did not understand the class distinction among the hobbits. I knew that they were on unequal social footing, what with Sam working for Frodo, but I did not really have an appreciation of how this impacted the interactions between the hobbits. Most of the instances where Sam adopts a deferential or submissive attitude which many adults would discern as a marker of his lower-class status, conveyed a much different meaning to me. I saw in these instances the actions of a young boy who was uncertain of the world and his place in it. Therefore, Sam’s appeal to Frodo in his first scene with dialogue, his “Don’t let him hurt me, sir!” (FR, I, ii, 63), struck me as a plea to someone with more understanding of the situation, not as a petition to someone of higher social distinction. This interpretation pairs well with Sam’s expressions of unbridled joy and sense of adventure in a way that makes him seem young and naive. In the same scene, Sam’s ability to change to “Me go and see Elves and all! Hooray!” in just a few lines is very characteristic of the way these two currents of Sam’s personality intersect to make him seem young (FR, I, ii, 64).

In a similar fashion, I interpreted the other hobbits using this same lens. Merry’s “know-it-all” personality came across as a child whose ignorance enabled their over-confidence. Pippin’s joviality struck me as a “cut-up,” someone who was always trying to make others laugh and be the center of attention. The best scene to quickly illuminate both interpretations is the exchange between them in the Prancing Pony just before Frodo, Pippin, and Sam head into the common room. Merry warns the others to “mind your Ps and Qs, and don’t forget that you are supposed to be escaping in secret, and are still on the high-road and not very far from the Shire” (FR, I, ix, 154). To which Pippin responds “Mind yourself! Don’t get lost, and don’t forget that it is safer indoors” (FR, I, ix, 154). Merry’s warning comes from a place of superiority. He feels like he knows more than the other hobbits, and it is his burden to keep them in-line, even though he has never been much farther than they have and has only heard tales of Bree. Pippin’s response starts with a rebuttal. He starts indicating that Merry should be as wary as they are, and goes on to give his own warnings. Pippin’s warnings are a mockery of Merry’s in that they expose the unnecessary statements of common sense for what they are. This shows Merry’s high self-regard and Pippin’s playful way of bringing him back down to hobbit stature.

The final scene I want to talk about is the interaction in “Three is Company” where Pippin orders Sam to prepare breakfast for the others after their first night camping in the Shire. The following exchange takes place:

[Frodo] stretched. “Wake up, hobbits!” he cried. “It’s a beautiful morning.”

“What’s beautiful about it?” said Pippin, peering over the edge of his blanket with one eye. “Sam! Get breakfast ready for half-past nine! Have you got the bath-water hot?”

Sam jumped up, looking rather bleary. “No, sir, I haven’t, sir!” he said.

Frodo stripped the blankets from Pippin and rolled him over, and then walked off to the edge of the wood. (FR, I, iii, 72)

I choose this scene for a couple of reasons. Again, remember that I was unaware of the class distinction as a young reader. This scene, then, demonstrated the kind of hierarchy of joking that can persist within a friend-group. Pippin’s entitlement leads him to order Sam around and Sam, as the stereotypical member of the group who is seeking belonging, is quick to accommodate the demand. In a sense, I considered this a joke from Pippin that he took too far. This crossing of a line is what compels Frodo to stick up for their mutual friend and check Pippin, much like Pippin does to Merry in the Prancing Pony scene discussed above. It would not have surprised me, in my initial read, if Pippin directed this command at Frodo; though I would have expected Frodo to stand up for himself had that been the case.

The only exception to this form of stereotyping was Frodo. Frodo was a very difficult character for me to understand as a young first-time reader. He was very complex, too complex for me to really grasp much of until I read the book a second time as a teenager. While he was on the same level with the other hobbits, meaning they treated him as an equal, he was altogether more grave and serious than the rest of them. I almost want to say that I approached Frodo as the “straight man” of the group. He was the one who understood the larger situations so he endured the colorful expressions of delight and humor without engaging in them himself very often. I was much more engrossed by Frodo’s character later in the book, but I did not particularly like him this early on—even though I probably identified more with him on a personal level than any of the other hobbits. His reserved demeanor and aloof personality among the inhabitants of the Shire were very relatable for an introverted middle-schooler.

Where do We Go From Here?

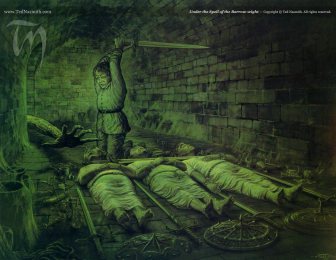

I hope to stop by Farmer Maggot’s pretty soon, then explore the Barrow Downs!

What Do You Think?

Did you equate the hobbits with a specific age when you read LotR? If so, what age were they?

How has your mental-image of the hobbits changed over your experience rereading/discussing LotR?