This is one in a series of posts where the content is provided by a guest who has graciously answered five questions about their experience as a Tolkien reader. I am very humbled that anyone volunteers to spend time in this busy world to answer questions for my blog, and so I give my sincerest thanks to Julie and the other participants for this.

To see the idea behind this project, check out this page

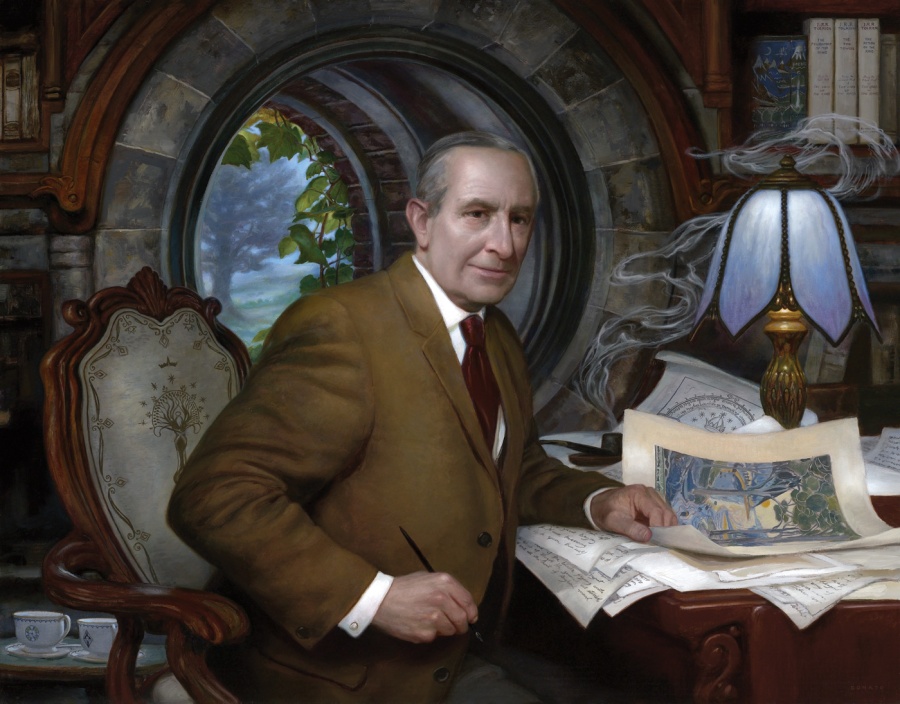

I want to thank Donato Giancola for allowing me to use his stunning portrait of J.R.R Tolkien as the featured image for this project. If you would like to purchase print of this painting, they are available on his website!

If you would like to contribute your own experience, you can do so by using the form on the contact page, or by emailing me directly.

Now, on to Julie Valdez’s responses:

How were you introduced to Tolkien’s work?

I first heard of J.R.R. Tolkien when I was about ten. A classroom that I was in for the after school program was reading The Hobbit, and I used to stare at the cover wondering how the author’s last name was pronounced. I read a Tolkien work for the first time the following year because my teacher had a copy of The Two Towers lying around. Unfortunately, I only read three pages before I gave up, as I had no idea who the characters were or what in the world an orc was. Fortunately, three years later, I read the entire series for the first time.

What is your favorite part of Tolkien’s work?

To me, the best part of Tolkien’s work is how very inspiring his writing is. The small have the strongest will. Men are frail, but resilient. The love of friends can help you conquer. Hope is a light in the darkness. Tolkien gave me hope in a time where I had none, and so the inspiration his writing blessed me with has been the best part for me.

What is your fondest experience of Tolkien’s work?

My fondest experience of Tolkien’s work was reading The Hobbit with my little sister. I was thirteen and she was eight at the time, and so in a way, I felt like I was passing something on to her, this love for Middle-earth and admiration for this author. We had so much fun reading that together, and when her class read The Hobbit the following year, she knew even more about the book than the teacher did! In a way, this love that we share for Middle-earth is a special connection, because we don’t know many Tolkien fans our age, so Middle-earth became our special little niche. We had each other to share it with, and it all began with the day she asked me to read her The Hobbit.

Has the way you approach Tolkien’s work changed over time?

My approach has changed only a bit. I’ve become so familiar with several of Tolkien’s works that my time rereading has become more of re-analyzation and searching for things that I missed since the last time I read.

Would you ever recommend Tolkien’s work? Why/Why not?

I recommend Tolkien to everyone. First of all, I am an avid advocate for the classics, and I think that everyone should read The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings before they go to college. Second, Tolkien has a very unique approach to fantasy where he borrows from several different mythologies that is very enriching to readers. Third, Tolkien writes unlike any author that I have ever read before. He dedicated his life to fantasy, and his works have a profound resonance that you rarely see anymore as a result. Fourth, whether or not you are a huge fan of the fantasy genre, you can always find something from Tolkien that will suit your fancy. For the fantasy reader, there’s his Middle-earth saga. For those who prefer non-fiction, he has written several engaging essays. For the poetic soul, there are enough songs and poems of several themes to make an anthology. For the little ones, there’s The Hobbit and other light-hearted works like Letters from Father Christmas and Farmer Giles of Ham. Sixth, Tolkien wrote from the human soul, and as a result, his works are felt in the soul. His characters are so complex and human-like that you will most certainly find a plight or characteristic that strikes a chord with you. I just feel that J.R.R. Tolkien was a gift to the world, and that the gifts he left behind ought to be shared, especially in a time where the fantasy genre and writing in general is taking a somewhat unsavory turn.

nfluence of J.R.R. Tolkien on conceptions of the Middle Ages and medieval prevalent in academic and popular cultures. As has been amply attested, Tolkien’s medievalist work in his Middle-earth corpus has exerted an outsized influence on subsequent fantasy and medievalist popular culture, and, following Paul B. Sturtevant’s assertions in The Middle Ages in Popular Imagination, it is largely or chiefly through popular cultural engagement with the materials that people—both the general public and those who become the students and scholars of the medieval—develop their early understandings of the Middle Ages. Decades on, Tolkien’s influence on popular culture—books, yes, but also movies, tabletop games, video games, television series, music, and other elements of popular understanding—continues to be felt, and continued examination of that influence is therefore warranted.

nfluence of J.R.R. Tolkien on conceptions of the Middle Ages and medieval prevalent in academic and popular cultures. As has been amply attested, Tolkien’s medievalist work in his Middle-earth corpus has exerted an outsized influence on subsequent fantasy and medievalist popular culture, and, following Paul B. Sturtevant’s assertions in The Middle Ages in Popular Imagination, it is largely or chiefly through popular cultural engagement with the materials that people—both the general public and those who become the students and scholars of the medieval—develop their early understandings of the Middle Ages. Decades on, Tolkien’s influence on popular culture—books, yes, but also movies, tabletop games, video games, television series, music, and other elements of popular understanding—continues to be felt, and continued examination of that influence is therefore warranted.